eStoreRx™

Online Supplement Dispensary

eStoreRx™ is an easy direct-to-patient ordering & fulfilment program for lifelong wellness.

For 50 years, Biotics Research Corporation has revolutionized the nutritional supplement industry by utilizing “The Best of Science and Nature”. Combining nature’s principles with scientific ingenuity, our products magnify the nutritional

eStoreRx™ is an easy direct-to-patient ordering & fulfilment program for lifelong wellness.

Biotics Research is proud to expand our commitment to education with the Wellness Unfiltered Pro Podcast. Each episode delves into key health topics and the clinical applications of our premier products. Through candid, insightful conversations, our team offers practical guidance to keep you informed and empowered as a healthcare professional.

March 03 2026

Anyone who’s struggled with their weight—or who sees patients who do—knows that the long-term outlook isn’t exactly encouraging. As difficult as it ca...

“We are what we eat” should actually say, “We are what our microbes eat.” In fact, what we eat immediately and profoundly influences our gut microbiome, which then determines our health.

“We are what we eat” should actually say, “We are what our microbes eat.” In fact, what we eat immediately and profoundly influences our gut microbiome, which then determines our health.

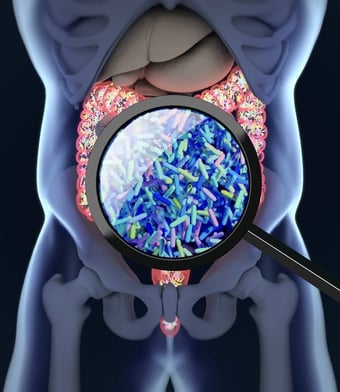

With trillions of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa, taking residence in our guts, it’s no surprise they play significant and precise roles in our overall health. Research reveals a number of disease states linked to the landscape of the microbiome. IBD patients, for example, tend to have less bacterial diversity than normal. They also have a lower quantity of butyrate-producing bacteria. A recent study showed that the bacteria in our guts can also produce amyloid and lipopolysaccharides, both instrumental in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Interest in pioneering into the microbiome’s influence on our health piqued when the two most predominant bacterial groups – gram positive Firmucutes and gram negative Bacteroidetes – were found to play a role in obesity. In short, when the ratio between the two bacteria shifted towards a higher abundance of Firmicutes, a subject was found to be more prone to obesity. Research took that knowledge a step further, transplanting the “obese” bacteria into a host, only to discover the host also became obese, which propelled our journey into gut microbiome engineering.

Today, we understand that we don’t need to be passive about the make-up of our gut flora, but instead, can take action to engineer our guts to be home to the bacteria that will most benefit us. Probiotics supplementation increases each year, with the number of Americans using probiotics quadrupling from 2007 to 2012. Fecal transplants also gained credibility as an effective and safe intervention for re-engineering the microbiomes of patients, particularly those diagnosed with relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. However, it can prove challenging when finding donors and producing the preparations. Rather than invest in inoculating the gut with someone else’s bacterial soup to force health benefits, a recent review in the Journal of Translational Medicine highlighted how foods vastly and immediately affect the gut microbiome. What we eat affects our gut bacteria? Sounds obvious and simplistic, but these researchers identified how particular types of food produced predictable shifts in the gut flora.

The review limited its research to human studies published between 1970 and 2015, and evaluated 188 articles that fit the criteria of how dietary intervention affected microbial composition.

1 Protein – Overall, protein consumption was found to be positively correlated with bacterial diversity in the gut. Whey and pea protein increased both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, while whey also decreased Bacteroides fraglis and Clostridium perfringens, both pathogenic.

Additionally, pea protein was found to increase short chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels, which are considered anti-inflammatory, and play a role in mucosal integrity. One study, however, found that a high animal protein/low carbohydrate diet resulted in reduced Roseburia and Fubacterium rectale, both beneficial bacteria. Animal protein can be high in fat, and fats also influence the gut microbiota.

In summary, this review confirmed that diet is our first line of offense and defense in engineering a microbiome that will foster overall health. After looking at various diets ranging from the “Western” diet to the vegan diet, the researchers determined a Mediterranean-Type Diet, replete with its beneficial fatty acids, high amounts of fiber, high levels of polyphenols and greater ratio of vegetable to animal protein, to be the most preferred by the beneficial bacteria.

Related Biotics Research Products: ![]()

Submit this form and you'll receive our latest news and updates.

The vagina hosts a dense and distinct microbial ecosystem, comprising approximately 10¹⁰–10¹¹ bacteria. These microbiota...

Learn moreCompelling evidence has been uncovered outlining the relationship between coffee consumption and the composition of the ...

Learn moreA growing body of evidence suggests that the gut microbiome plays a role in the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases, ...

Learn more

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product has not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

© 2025 Biotics Research Corporation - All Rights Reserved

Submit your comment